Logistically unable to support a long siege of the walled city of Kadesh, Ramesses prudently gathered his troops and retreated south towards Damascus and ultimately back to Egypt. Once back in Egypt, Ramesses proclaimed that he had won a great victory, but in reality, all he had managed to do was to rescue his army since he was unable to capture Kadesh. In a personal sense, however, the Battle of Kadesh was a triumph for Ramesses since, after blundering into a devastating Hittite chariot ambush, the young king had courageously rallied his scattered troops to fight on the battlefield while escaping death or capture. The new lighter, faster, two-man Egyptian chariots were able to pursue and take down the slower three-man Hittite chariots from behind as they overtook them. The leading elements of Hittite's retreating chariots were thus pinned against the river and in several hieroglyphic inscriptions related to Ramesses II, said to flee across the river, abandoning their chariots, "swimming as fast as any crocodile" in their flight.

Hittite records from Boghazkoy, however, tell a very different conclusion to the greater campaign, where a chastened Ramesses was forced to depart from Kadesh in defeat. Modern historians essentially conclude the battle was a draw, a great moral victory for the Egyptians, who had developed new technologies and rearmed before pushing back against the years-long steady incursions by the Hittites, and the strategic win to Muwatalli II, since he lost a large portion of his chariot forces but sustained Kadesh through the brief siege.

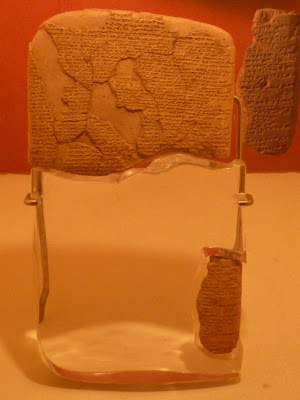

The Kadesh peace agreement—on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum—is believed to be the earliest example of any written international agreement of any kind.

The Hittite king, Muwatalli II, continued to campaign as far south as the Egyptian province of Upi (Apa), which he captured and placed under the control of his brother Hattusili, the future Hattusili III. Egypt's sphere of influence in Asia was now restricted to Canaan. Even this was threatened for a time by revolts among Egypt's vassal states in the Levant, and Ramesses was compelled to embark on a series of campaigns in Canaan in order to uphold his authority there before he could initiate further assaults against the Hittite Empire.

In his eighth and ninth years, Ramesses extended his military successes; this time, he proved more successful against his Hittite foes when he successfully captured the cities of Dapur and Tunip, where no Egyptian soldier had been seen since the time of Thutmose III almost 120 years previously. His victory proved to be ephemeral, however. The thin strip of territory pinched between Amurru and Kadesh did not make for a stable possession. Within a year, they had returned to the Hittite fold, which meant that Ramesses had to march against Dapur once more in his tenth year. His second success here was equally as meaningless as his first, since neither Egypt nor Hatti could decisively defeat the other in battle.

The running borderlands conflicts were finally concluded some fifteen years after the Battle of Kadesh by an official peace treaty in 1258 BC, in the 21st year of Ramesses II's reign, with Hattusili III, the new king of the Hittites. The treaty that was established was inscribed on a silver tablet, of which a clay copy survived in the Hittite capital of Hattusa, in modern Turkey, and is on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. An enlarged replica of the Kadesh agreement hangs on a wall at the headquarters of the United Nations, as the earliest international peace treaty known to historians. Its text, in the Hittite version, appears in the links below. An Egyptian version survives on a papyrus.

Hittite records from Boghazkoy, however, tell a very different conclusion to the greater campaign, where a chastened Ramesses was forced to depart from Kadesh in defeat. Modern historians essentially conclude the battle was a draw, a great moral victory for the Egyptians, who had developed new technologies and rearmed before pushing back against the years-long steady incursions by the Hittites, and the strategic win to Muwatalli II, since he lost a large portion of his chariot forces but sustained Kadesh through the brief siege.

The Kadesh peace agreement—on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum—is believed to be the earliest example of any written international agreement of any kind.

The Hittite king, Muwatalli II, continued to campaign as far south as the Egyptian province of Upi (Apa), which he captured and placed under the control of his brother Hattusili, the future Hattusili III. Egypt's sphere of influence in Asia was now restricted to Canaan. Even this was threatened for a time by revolts among Egypt's vassal states in the Levant, and Ramesses was compelled to embark on a series of campaigns in Canaan in order to uphold his authority there before he could initiate further assaults against the Hittite Empire.

In his eighth and ninth years, Ramesses extended his military successes; this time, he proved more successful against his Hittite foes when he successfully captured the cities of Dapur and Tunip, where no Egyptian soldier had been seen since the time of Thutmose III almost 120 years previously. His victory proved to be ephemeral, however. The thin strip of territory pinched between Amurru and Kadesh did not make for a stable possession. Within a year, they had returned to the Hittite fold, which meant that Ramesses had to march against Dapur once more in his tenth year. His second success here was equally as meaningless as his first, since neither Egypt nor Hatti could decisively defeat the other in battle.

The running borderlands conflicts were finally concluded some fifteen years after the Battle of Kadesh by an official peace treaty in 1258 BC, in the 21st year of Ramesses II's reign, with Hattusili III, the new king of the Hittites. The treaty that was established was inscribed on a silver tablet, of which a clay copy survived in the Hittite capital of Hattusa, in modern Turkey, and is on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. An enlarged replica of the Kadesh agreement hangs on a wall at the headquarters of the United Nations, as the earliest international peace treaty known to historians. Its text, in the Hittite version, appears in the links below. An Egyptian version survives on a papyrus.

The text is here

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento